On average, Canadian schools, primary and secondary, are better than American schools. When we arrived in Canada from Cape Town, South Africa (in the good old days of high standards), my daughter had to be bumped up two years. Had we emigrated straight to the USA, it would have been three years, easily. A 12-year old South African would have been in class with 15 year-old Americans.

A US-based correspondent for The Economist confirms that, “After two years of school in England, our six-year-old was so far ahead of his American peers that he had to be bumped up a year, where he was also ahead.” And his child was in a “good” American school!

In fact, as our author notes, “At 15, children in Massachusetts, where education standards are higher than in most states, are so far behind their counterparts in Shanghai at math that it would take them more than two years of regular education to catch up.” UPDATE: (8/9/021): This last fact is enormously telling. Our best schools are un-competitive with the best in the world.

At the heart of the problem is an educational ethos that prizes building self-esteem over academic attainment. This is based on a theory that self-confidence leads to all manner of other virtues, including academic achievement, because children who feel good about themselves will love learning – right? Not entirely.

American children came top at thinking they were good at maths, but bottom at maths.

I covered the self-esteem cult for kids as far back as the year 2000, when I had reviewed the book of a brilliant Canadian professor by the name of Marilyn Bowman.

In a 1997 monograph, Bowman forewarned that, while “every kind of social problem is analyzed as the outgrowth of low self esteem,” and while “treatment programs to teach people how to love themselves are put forward as the means of raising self-esteem,” not only is “the relationship between emotion and well being not robust, causal or meaningful,” but, on the contrary, there is a dark side to self-esteem. “The prototype aggressor,” explains Bowman, “is a man whose self-appraisal is unrealistically positive.”

American kids have dangerously elevated self-esteems. Drumming up feel-good ignorance can be risky business.

Concludes the Economist in 2016:

American children came top at thinking they were good at maths, but bottom at maths. For Korean children, the inverse was true: they considered themselves poorer at maths than the children of any other country, but were the best. The OECD study, similarly, found that American children believe they are good at maths and, indeed, are adept at very simple sums; but give them something halfway tricky and they struggle.

This is perverse. The self-esteem movement is drenched in the language of mutual respect; yet encouraging in children an inflated idea of their accomplishments is not respectful at all. It is delusional.

READING:

On the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) two-thirds of American children were not proficient readers.

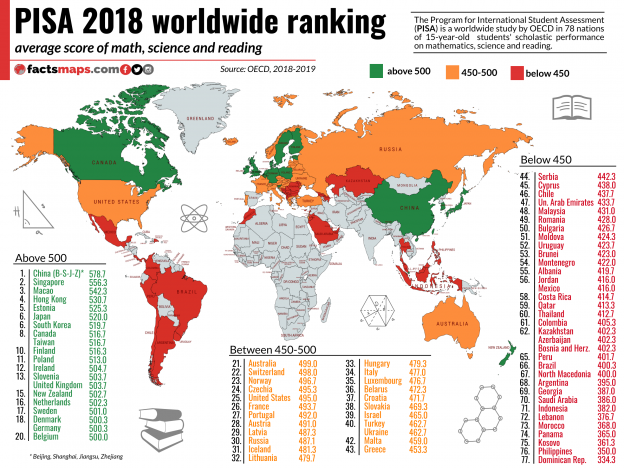

The most recent PISA test was given in 2018 to 600,000 15-year-olds in 79 education systems around the world, and included both public and private school students. In the United States, a demographically representative sample of 4,800 students from 215 schools took the test, which is given every three years.

Although math and science were also tested, about half of the questions were devoted to reading, the focus of the 2018 exam. Students were asked to determine when written evidence supported a particular claim and to distinguish between fact and opinion, among other tasks.

The top performers in reading were four provinces of China — Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang. Also outperforming the United States were Singapore, Macau, Hong Kong, Estonia, Canada, Finland and Ireland. The United Kingdom, Japan and Australia performed similarly to the United States.

print

print

Not surprising. I think the decline has been going on for a long time. When I entered a well-ranked STEM university in 1974, I suffered a pretty bad first quarter, as did a number of other aspiring engineers. Those of us who survived all had to agree that college improved as soon as we accepted that it was not just the 13th grade. I did note that the guys who’d graduated from Catholic (boys) high schools seemed to have a better grasp of what to expect. The colleges back then were still trying to uphold standards—they brought in a lot of serious students from foreign countries. They didn’t care that you had grown up with The New Math, or that McGuffey Readers had been eliminated. You better be able to read and write and do derivatives and integrals.

Now, I’m not so sure they hold to the same standards. In the late 70s, with a mere bachelors degree I was able to get a good job with a major aerospace company. Many did. Few engineers went to graduate school, which seemed like a path into academia in those days. A bachelors degree in engineering from that era was sufficient to ensure that the holder could be trained to handle virtually all of the tasks needed to put an aircraft aloft. If an engineer went to grad school at that time, it was almost always to get an MBA. These days, I notice that companies hire new graduates already possessing a master’s in engineering, and those that only have a bachelors degree, are all planning to get a master’s. It would seem the extra credential is needed for basic assurance. Just as UPS only hires people for delivery jobs who are college graduates. With them, their needs are a little more basic. The degree, they believe, gives them some assurance that the employee can read an address.