“White racial consciousness comes out … in such beliefs as the evil of reverse discrimination—whites being discriminated against because of the colour of their skin. Such views are NOT racist in the classic sense of white superiority.”—The Economist

The Economist, to which I subscribe because of its impeccable, intelligent reporting, offers quite a fair and incisive look into “the souls of white folks,” a glimpse you’ll not find in an American liberal magazine or other parrot-cage liners. (Palatial parrot cage, in the case of Oscar-Wood)

The story of race in America is usually about African-Americans and, more recently, Hispanics and Asians. But it is also about whites.

I excerpt from The Economist’s “White Americans are beginning to realise that they too belong to a race: Anxiety about their country’s demography is fuelling the politics of racial backlash” (May 22, 2021):

“… When it comes to their own race, white Americans divide into two tribes. As left-leaning whites become more conscious of racism, they also think more about what it means to be white. Six months after Mr Floyd’s death, 30% of whites told a poll run by Ipsos that they had “personally taken actions to understand racial issues in America”. …

… widespread is a feeling of some responsibility for the plight of African-Americans. Between 2014 and 2019, the share of whites who thought the government should spend more money on improving the conditions of African-Americans increased from 24% to 46%.The second white tribe is different. Over the past decade, according to calculations by Bill Frey of the Brookings Institution, a think-tank, the number of Americans who describe themselves as Latino or Hispanic, Asian, African- or Native American (plus those who identify as from two or more races) has risen by 53%. Over the same period America’s white population grew by less than 1%.

When he was running for the Senate in Texas in the mid-1960s, George H.W. Bush opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act because it “was passed to protect 14% of the people”. He said “I’m also worried about the other 86%.” Ronald Reagan took the same line when running for governor of California. Richard Nixon, while pushing policies that benefited African-Americans, said that minorities were “undercutting American greatness”, a familiar refrain. An unease over demographic transformation now plays a similar role in politics to the backlash against civil rights 50 years ago.

By 2005 the Republican Party had disowned its “southern strategy” of prising white Southerners away from the Democrats. “Some Republicans gave up on winning the African-American vote, looking the other way or trying to benefit politically from racial polarisation,” the party chairman told the NAACP pressure-group. “I am here today as the Republican chairman to tell you we were wrong.” Three years later America elected its first black president. Michael Tesler of the University of California, Irvine, notes that Barack Obama’s victory set off a fresh exodus of whites away from the Democrats. “It took the election of the first black president for some white Americans to work out that the Democratic Party is the party of non-whites,” he says. By 2020 the Republican Party’s lead among white men without a college degree was huge: they backed Mr Trump by a margin of 40 points.

These voting patterns did not reflect only fondness for tax cuts or a dislike of immigration, the most recognisable bits of Mr Trump’s pitch. They also reflected a view of race. According to Ashley Jardina of Duke University, 30-40% of whites say their racial identity is “very important”. This is far lower than the share of black or Hispanic Americans saying the same. But this group of race-conscious whites, who also say they have “a lot” or “a great deal” in common with other whites, numbers about 75m people of voting age. That makes them more numerous than any minority.

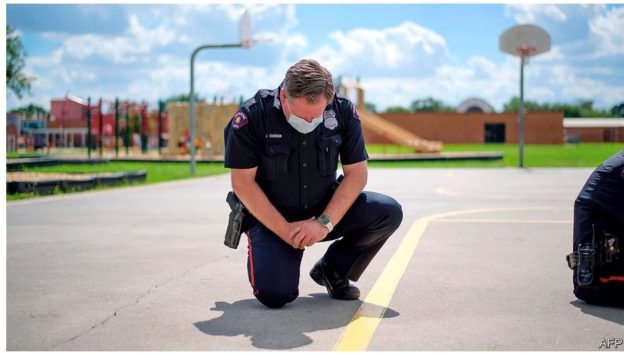

White racial solidarity has a murderous past. Recently it has been associated with tiki torches, neo-Nazis and the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017. Yet only a tiny fraction of white Americans share such extreme views. The sense of solidarity among whites described by Ms Jardina is broader. In her book “White Identity Politics”, she says that “white identity” is not a polite way of saying “dislike toward other racial or ethnic minorities”. White racial consciousness comes out instead in such beliefs as the evil of reverse discrimination—whites being discriminated against because of the colour of their skin. Such views are not racist in the classic sense of white superiority. Those who hold them reject anti-black stereotypes. But they are likely to discount the effects of past racism, and to believe that African-Americans would catch up with whites if only they worked harder. Like Mr Kroll, the police-union boss, who complained that Democrats accuse those who disagree with them of being racist, or Mr Trump, who claimed to be “the least racist person anywhere in the world”, many are acutely sensitive to accusations of racism.

As America becomes more multiracial, and whites lose the status of dominant group, their sense of racial solidarity may grow and the taboo against white pride may fade. A recent attempt to launch an Anglo-Saxon caucus by Republican House members could be a portent. Already many rural and suburban whites, who in Minnesota might have defined themselves as Swedes or Germans as well as Americans, define themselves as white. They, not Minnesota’s African-Americans, now live in the most racially segregated places of all.

This second white tribe thinks more like a minority than part of the country’s biggest single group. Geographic separation can lead to a reflexive bias that is different from racism in the 1950s but still lethal.”

MORE: “White Americans are beginning to realise that they too belong to a race”

print

print