Direct your righteous hatred appropriately, readers. Before anything else, what you need to know about Aruna Khilanani are these salient points:

Someone in authority invited this scum of the earth to give a talk to the nation’s top university (an intellectual shithole, in reality): Yale.

Someone in authority approved of, even liked, the topic of this vile, hideous woman’s address: “The Psychopathic Problem of the White Mind.” A diatribe of a morally diabolical individual, a psychiatrist, whose license to ply her craft on the public should be revoked.

A system designed to marginalize you and many other fine people selected Aruna Khilanani to train as a healer, a psychiatrist, and to minister to others.

This mental terrorist (with aspirations to practice terrorism on whites) has been put through America’s professional ringer. Aruna Khilanani is a product of America: She has come out of the educational system and has been approved by assorted medical bodies and institutions to practice her profession.

Someone thought that a person who wants to take medicine to “where [it] intersects [with] race, gender, politics, sexuality, and class” was fit to be unleashed on a vulnerable subset of society: psychiatric patients.

This must be the focus of your ire: The American system and the people who currently man it.

Now that you know where to focus your fury, read on about what Ugly In American, Aruna Khilanani, enabled by American institutional rot—a contemptible, irredeemably vile, empty human being—was espousing from a top American academic institution:

A few weeks ago, someone sent me a recording of a talk called “The Psychopathic Problem of the White Mind.” It was delivered at the Yale School of Medicine’s Child Study Center by a New York-based psychiatrist as part of Grand Rounds, an ongoing program in which clinicians and others in the field lecture students and faculty.

When I listened to the talk I considered the fact that it might be some sort of elaborate prank. But looking at the doctor’s social media, it seems completely genuine.

Here are some of the quotes from the lecture:

- This is the cost of talking to white people at all. The cost of your own life, as they suck you dry. There are no good apples out there. White people make my blood boil. (Time stamp: 6:45)

- I had fantasies of unloading a revolver into the head of any white person that got in my way, burying their body, and wiping my bloody hands as I walked away relatively guiltless with a bounce in my step. Like I did the world a fucking favor. (Time stamp: 7:17)

- White people are out of their minds and they have been for a long time. (Time stamp: 17:06)

- We are now in a psychological predicament, because white people feel that we are bullying them when we bring up race. They feel that we should be thanking them for all that they have done for us. They are confused, and so are we. We keep forgetting that directly talking about race is a waste of our breath. We are asking a demented, violent predator who thinks that they are a saint or a superhero, to accept responsibility. It ain’t gonna happen. They have five holes in their brain. It’s like banging your head against a brick wall. It’s just like sort of not a good idea. (Time stamp 17:13)

- We need to remember that directly talking about race to white people is useless, because they are at the wrong level of conversation. Addressing racism assumes that white people can see and process what we are talking about. They can’t. That’s why they sound demented. They don’t even know they have a mask on. White people think it’s their actual face. We need to get to know the mask. (Time stamp 17:54)

Here’s the poster from the event. Among the “learning objectives” listed is: “understand how white people are psychologically dependent on black rage.”

Also, here.

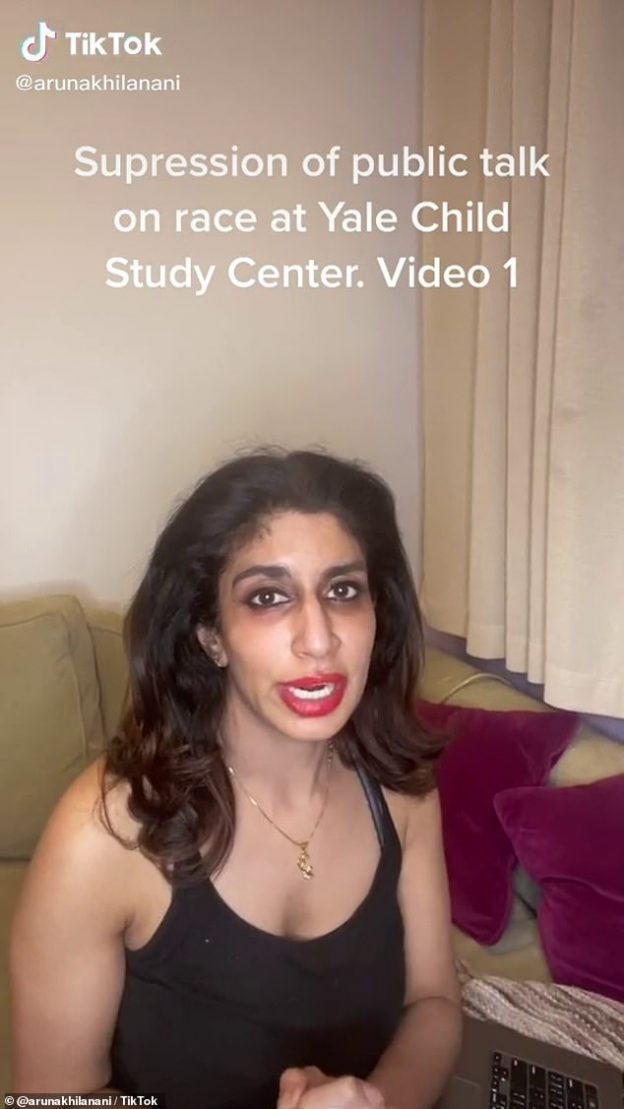

UPDATED (6/7/021): Khilanani, AKA “Ugly in America”, has more messages for whites:

Fox News featured her latest video rant in which Khilanani hissed, “Get it together white girls. There is a reason people hate you.”

I agree. It’s called the green-eyed monster, or envy for the illiterate.